by Specialdocs Consultants | Apr 1, 2022 | Medical Tests, Patient News, Staying Active, Wellness

Definitive Diagnostic Tool or Part of a Greater Health Matrix?

It’s an easily understood calculation: Body Mass Index, popularly known as BMI, computes an individual’s measure of body fat as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. Levels are defined as Underweight if less than 18.5, Normal weight if between 18.5 and 24.9, Overweight if between 25.0 and 29.9, and Obese if above 30. But what does BMI really tell us?

This simple formula has nonetheless sparked controversy and continued questioning: Is BMI a quick, easy and efficient way to identify weight problems and associated risk of disease in adults? Or is it an inaccurate measure because it doesn’t consider body composition, age, sex or ethnicity?

Years of debate, research and analysis now point to using BMI in a more nuanced way, suggesting that it is best employed as just one part of an initial health screening for individuals, and not as a diagnostic tool. Much more meaningful is how BMI fits with other essential measures of an individual’s health — blood pressure, blood sugar, cholesterol levels, heart rate, inflammation, physical activity, diet, cigarette smoking and family history.

Looking at BMI alone can be misleading when you consider that:

- Women tend to have more body fat than men.

- Older adults have more body fat than younger ones. Aging is associated with an unhealthy increase in body fat and an associated increased risk for prediabetes and type 2 diabetes.

- At the same BMI, the metabolic risks for people of Asian descent are higher than for Caucasians.

- People who engage in strength training two or more times per week have higher lean muscle mass than nonathletes, which can result in a higher BMI but not necessarily a higher risk of disease.

Additionally, knowing where the fat is distributed is essential in determining disease risk. The pear shape associated with women means subcutaneous fat around the hips, thighs and buttocks; more dangerous is the apple shape, which indicates visceral fat in the abdomen (waist circumference of more than 40 inches for men or more than 35 inches for nonpregnant women), which is linked to higher risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes.

An influential study published in Nature further revealed the flaws in categorizing people as “unhealthy” or “healthy” based on BMI alone. The authors found that more than 74 million American adults were miscategorized. Nearly half of people considered overweight and 29% of those categorized as obese were actually metabolically healthy, with normal blood pressure, cholesterol and blood glucose levels. Meanwhile, 30% of those considered “normal weight” had metabolic or heart issues.

The origins of BMI help explain its limitations. In the 1830s Belgian mathematician Lambert Adolphe Jacques Quetelet developed a test intended to identify the “l’homme moyen,” or the “average man,” by taking the measurements of thousands of Western European men and comparing them to find the ideal weight. More than a century later, American physiologist and dietician Ancel Keys promoted Quetelet’s Index as the best available way to quickly screen for obesity, identifying certain BMI ranges as associated with greater risk of disease and poor health outcomes. However, like Quetelet, Keys didn’t account for different body types or ethnicities.

One other point to consider: While more intrusive and not as commonly available, methods such as measuring skinfold thicknesses, bioelectrical impedance, underwater weighing, abdominal CT scans (for visceral fat) and dual-energy X-ray absorption are more accurate than BMI for estimating body fat.

So is BMI still meaningful?

As a discussion point, or as one tool used in combination with other assessments of metabolic and skeletal health, it can be useful.

Most importantly, body fat is just one of many factors considered when evaluating individual health and risk of disease.

We encourage you to call your healthcare provider to discuss your personal wellness profile.

by Specialdocs Consultants, LLC | Jul 7, 2020 | Medical Tests, Patient News

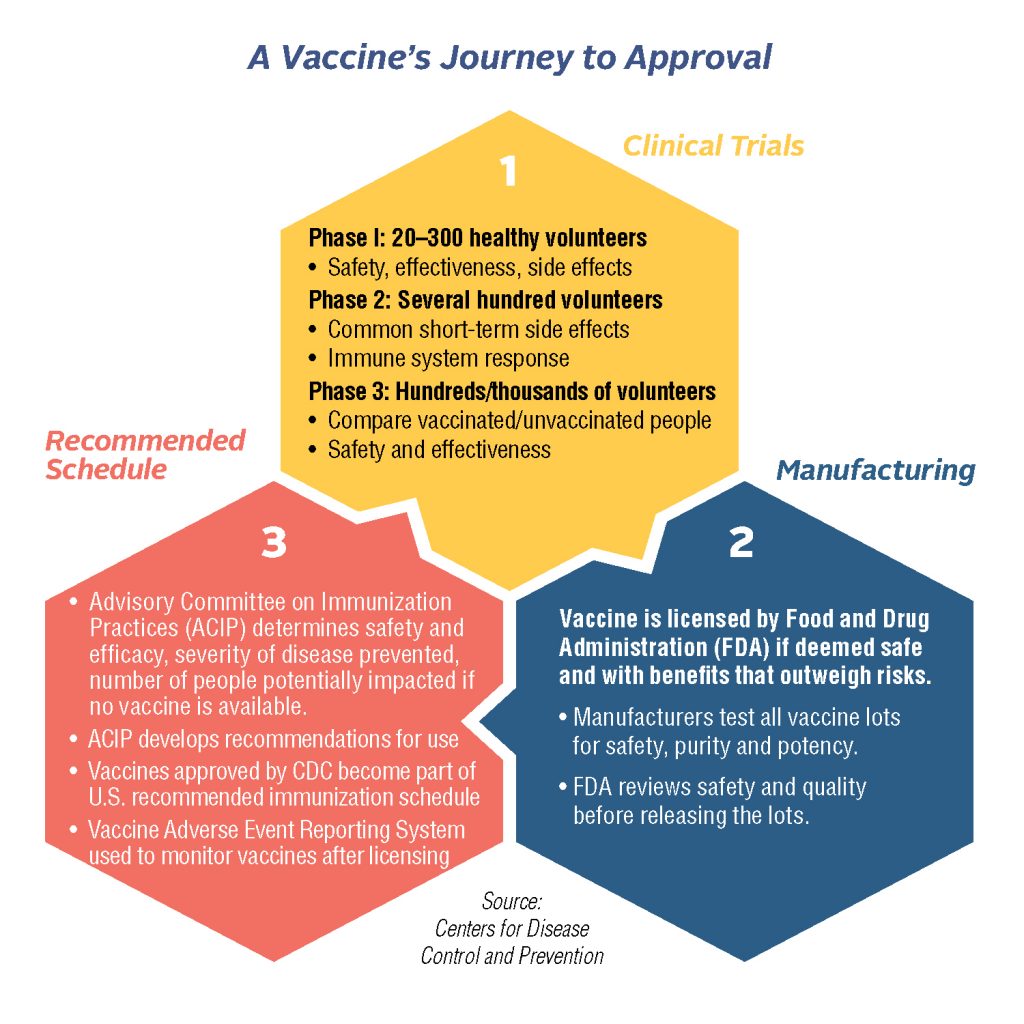

Expert Calls for Slow & Steady Approach in Vaccine Development

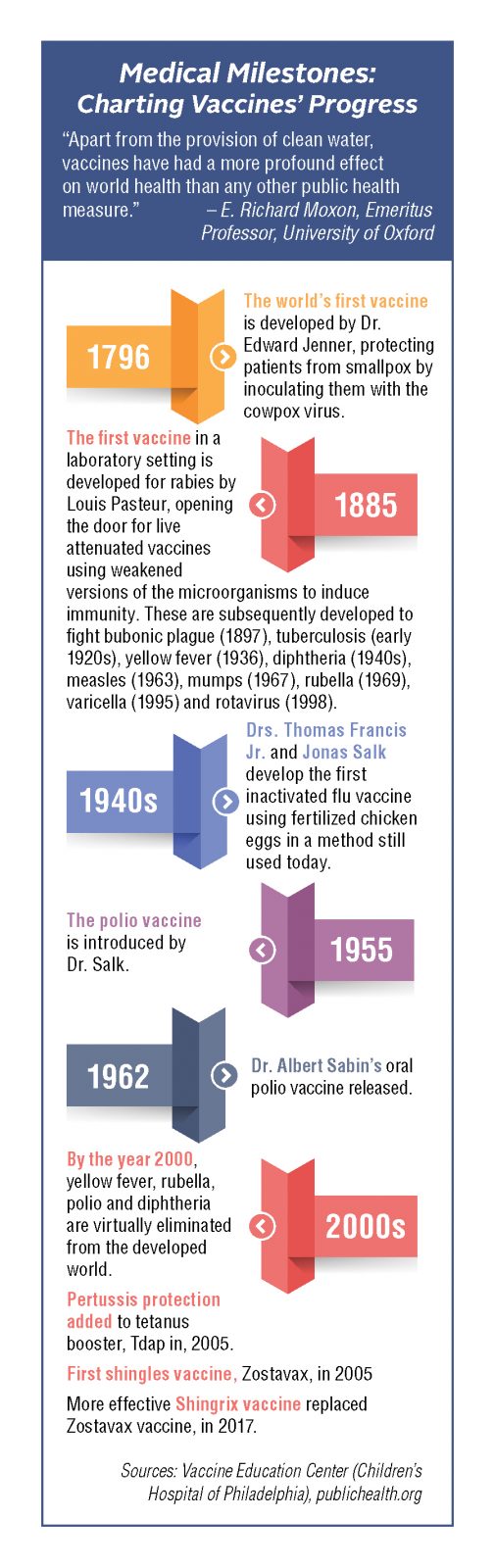

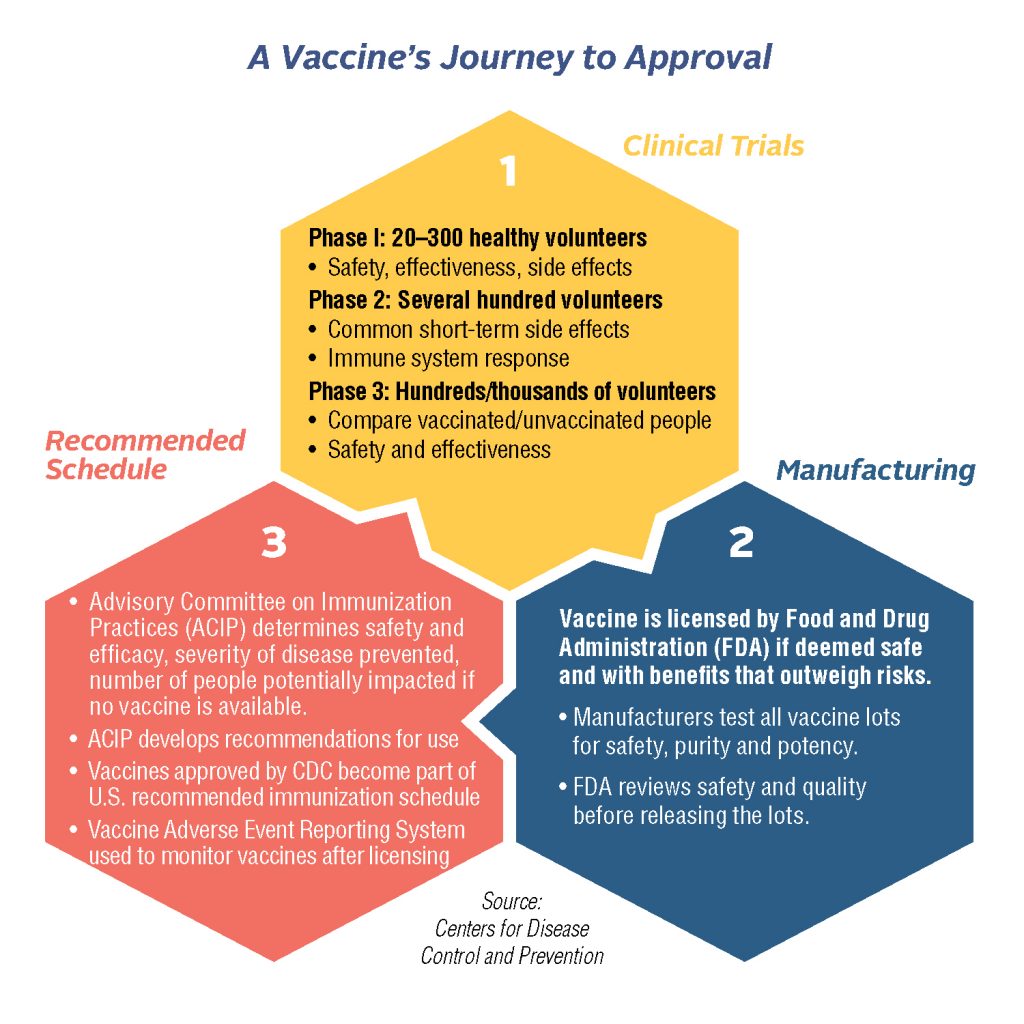

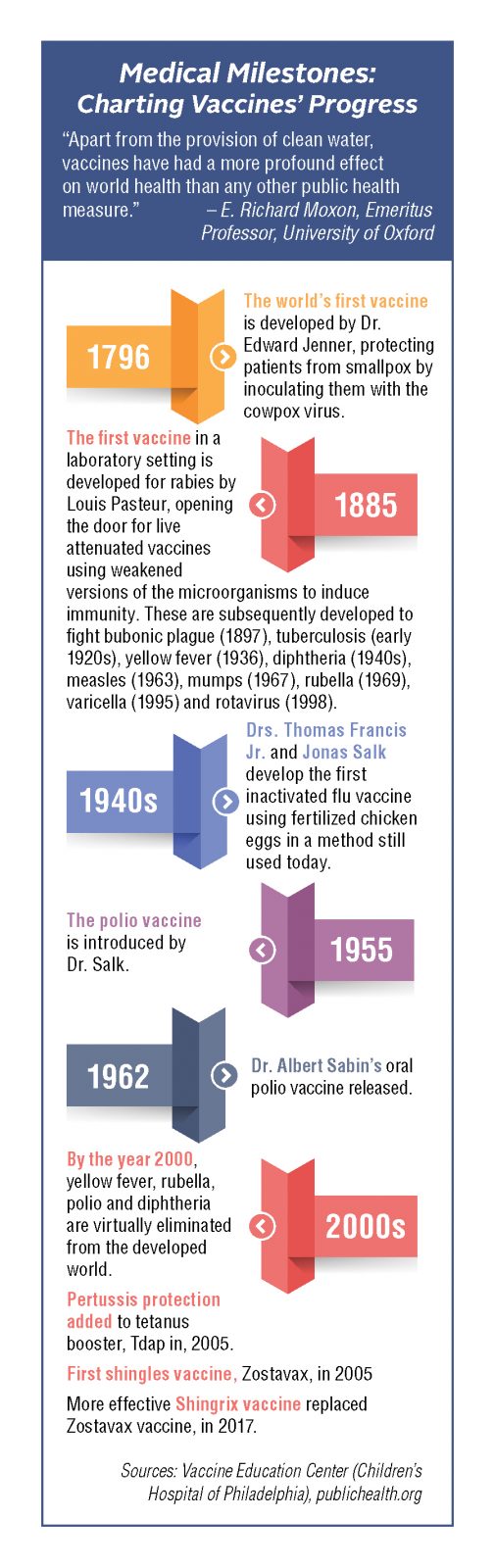

While the race to develop a coronavirus vaccine may seem as if it’s being run in slow motion, with most experts predicting a 2021 launch at earliest, by historical standards it’s unfolding with incredible swiftness. Looking back at timelines for other vaccines, it becomes evident that there are numerous reasons for a slow and steady approach, according to Michael Kinch, director of Washington University’s Centers for Research Innovation in Biotechnology and Drug Discovery. Kinch, who authored the authoritative book, Between Hope and Fear: A History of Vaccines and Human Immunity, cautions that vaccine development is a long, complex process requiring gathering of laboratory and real-world evidence and extensive evaluation.

“Testing for safety and efficacy requires considerable time, even with improved technology. We need to get this absolutely right, because if we panic and rush, there may be a price to be paid in terms of toxicity,” explains Kinch. “For example, in 1976, fear of a swine flu epidemic led to rapid development of a vaccine which caused Guillain-Barre syndrome [a paralyzing neurological disorder] in a small percentage of patients. That doesn’t normally happen if you take the time to check at each step.”

Lessons Learned from Past Vaccine Development

A salient lesson can be learned by going further back to the polio vaccine of the 1950s, according to Kinch. Long heralded as one of the 20th century’s landmark immunizations, it nevertheless encountered a problem when initially released. In a situation eerily similar to today’s coronavirus pandemic, the poliovirus’s paralyzing and often deadly effects were terrifying the nation, and the threat of prolonged quarantines as the only real mode of prevention had people desperate for a solution. In 1952, Dr. Jonas Salk began his clinical investigation of a polio vaccine, and the development and distribution schedule was significantly expedited to allow for release in 1955. Unfortunately, in the rush to launch, improper manufacturing of some of the early batches led to unnecessary outcomes.

The logistical challenges of rolling out a coronavirus vaccine will be significant, predicts Kinch.

“We need to manufacture enough of the vaccine to immunize 350 million Americans, but this will also require 350 million vials, syringes, stoppers and any other parts yet to be determined,” says Kinch. “This is fundamental to success, but we’re not fully looking it in the eye. And extending it to a world population of 7.5 billion makes it even more essential to address now.”

The stakes are enormous, as Kinch believes a successful coronavirus vaccine may have the power to change medicine for a generation.

“We’re going to rethink our approach just as we did with other epidemics which defined the 20th century from a scientific standpoint. Smallpox led to awareness of the importance of sanitation, and the vaccine which was developed eliminated the disease worldwide. Spanish flu gave us the structure of DNA and the foundations of biotechnology, and HIV-AIDS led us to focus on evidence-based science and government-sponsored clinical trials,” he says.

What can be learned through development of a safe, effective and scalable vaccine for the novel coronavirus may well parallel these important breakthroughs. As Kinch recently wrote: “Vaccines come with serious medical, social and political implications. If we anticipate and address them accordingly, the coming months and perhaps years could be among the finest hours for the United States and its people.”

The post Coronavirus Vaccine: Expert Says, ‘We Need Time to Get This Right’ appeared first on Specialdocs Consultants.

by Ivan | Jun 1, 2020 | Medical Tests, Patient News

Colorectal Cancer awareness could save your life.

As one of the country’s most preventable illnesses, with a readily available test that is both diagnostic and therapeutic, why does colorectal cancer (CRC) stubbornly remain the second-leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the US? The key to reducing deaths is in the colonoscopy, a direct visualization test of the entire colon that enables a physician who specializes in gastroenterology to screen for abnormal growths (polyps) and remove them before they turn cancerous. Fighting the colonoscopy fear factor through knowledge is critical.

Don’t let colonoscopy prep scare you away. Fighting the Colonoscopy Fear Factor is important to your health

For many people, the rigorous prep required to thoroughly clean out the colon the night before the test has overshadowed the colonoscopy’s lifesaving impact, resulting in a third of adults 50 or older, the group most at risk of developing colorectal cancer, to not be screened. The colonoscopy reputation deserves a major turnaround, because in 2020 the colonoscopy experience is highly manageable, with more palatable prep options, a pain-free procedure and swift reporting of results … so there’s no need to dread your colonoscopy or anxiously avoid a 10-year follow-up. You can fight the colonoscopy fear factor.

Previous prep involved drinking up to 128 ounces of salty-tasting fluid over a short time, but several new colon cleansing preparations are now available that require less fluid, according to Mayo Clinic. Products such as Prepopik, Suprep and Plenvu can be mixed with a liquid of choice, and some patients might be offered a nonprescription prep of polyethylene glycol (such as MiraLAX) followed by an electrolyte-containing drink (such as Gatorade) – but note that these lower-volume prep solutions may not be appropriate for people with heart, kidney or liver disease. If higher-volume fluid solutions are needed, a split dose makes it easier and more tolerable, with half of the laxative taken in one sitting and the other half on the morning of the procedure. Even newer possibilities are on the horizon: Keep an eye out for an edible colonoscopy prep kit that incorporates active laxative ingredients into better-tasting food bars and drinks, with final phase of trials scheduled in mid-2020.

Whatever type of solution you choose, adjust your diet a few days before your colonoscopy to include smaller portions and low-fiber foods to ensure a smoother prep. On the day before your procedure, when you’ll be on a liquid diet, treat yourself to good-tasting items like organic low-sodium broth, white grape juice, flavored sparkling waters and full-bodied coffee (without creamer). Make the prep solution more palatable by refrigerating and drinking it chilled; suck on a lemon wedge or chew a piece of gum between glasses to help mask the flavor. When the solution starts to work emptying your bowels, be prepared for your time in the bathroom with wet wipes or double ply toilet paper, a fully charged phone, and some light reading.

During the 30- to 60-minute procedure, most people will be given a mild sedative drug or an anesthetic to put them in a “twilight” sleep, while a few will require general anesthesia. A thin, flexible, lighted tube is inserted into the colon, and air, CO2, sterilized water or saline is gently pumped in to inflate the colon and allow the entire lining to be viewed. Polyps are removed if present, and biopsies are taken of any abnormal areas. After the test, you’ll recover from the sedative for about an hour before you go home and consider this mission accomplished.

Still feeling uneasy about a colonoscopy?

Noninvasive, stool-based screening tests may offer an alternative if you’re considered at average risk – that is, no family or personal history of CRC, no previous polyps, no long-standing inflammatory bowel disease or the presence of certain genetic syndromes. The most well-known is FDA-approved Cologuard, which detects DNA markers for cancer and uses fecal immunochemical testing (FIT) to find blood in the stool, with less reliable results: 92% accuracy for cancer and only 69% for advanced colon polyps, plus a 13% rate of false positives. Other options include a “virtual colonoscopy” that uses CT imaging for a detailed view of the inside of the colon and rectum or a flexible sigmoidoscopy to view the lower part of the colon, which requires the colon prep described above. However, a positive result on any of these tests will result in the need for a colonoscopy, which remains the gold standard for colon cancer testing as the most accurate way to find and remove polyps and determine the right follow-up intervals.

Under 50: Are Screenings Necessary?

For people with a family history of genetic conditions that put them at increased risk, screenings may be recommended at a younger age. Additionally, in 2018, a controversial decision was made by the American Cancer Society to lower its threshold to age 45, in response to a steady rise in the cancer’s prevalence each year since the mid-1990s among ages 20 to 54. A new 2020 study appeared to provide more evidence, showing a 46% spike in colorectal cancer incidence between ages 49 and 50 – attributed to cancer that had gone undetected in younger patients until routine screening at age 50.

Research is in progress to resolve the conflicting guidelines, but current best practices* keep 50 as the age to begin colorectal cancer screening for average-risk adults; with FIT or guaiac-based fecal occult blood testing every two years or a colonoscopy every 10 years; and no testing after age 75.

Did You Know?

More than 15 million colonoscopies are performed in the United States annually. Speaking with your doctor and being armed with the right information can make fighting the colonoscopy fear factor a little easier.

Recommendation:

We recommend all adults over the age of 40, with anemia, have a gastroenterology evaluation including colonoscopy. Please call our office for more information.

*American College of Physicians

The post Fighting the Colonoscopy Fear Factor appeared first on Specialdocs Consultants.

by Specialdocs Consultants, LLC | Jan 9, 2018 | Medical Tests, Patient News

20,000 and You: Unlocking the Genetic Code

In just the past few years, there has been a significant shift in the practical uses of genetic testing, which examines changes, or variants, in your genes that may lead to illness or disease. Once considered more of an investment in the future and less applicable to individual patient care, opportunities to guide health and lifestyle decisions in the here and now may be tantalizingly close at hand.

“Genetic testing is progressing from an occasionally deployed diagnostic tool to becoming the new founding architecture of a personal health record, and may ultimately become a vital addition to a patient’s clinical portfolio,” explains Calum MacRae, MD, geneticist, Chief of Cardiovascular Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and in private practice at Boston’s AllCare Medical, whose decades-long focus has been on how to systematically implement genomics discoveries into clinical care.

In broad strokes, three areas are identified through genetic testing: disease carrier states for genes, important to the patient’s immediate family; inherited diseases such as heart disease or cancer; and an emerging predictive utility for drug responses and risk of common diseases. This information forms the foundation of personalized medicine, targeted to a patient’s specific genetic profile. According to Dr. MacRae, a holistic approach will optimize the enormous potential of genetic testing, allowing physicians to engage all their patients to understand their own genomes and build collaborative plans for lifestyle modification, nutritional choices and medications that may prevent or delay disease.

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) testing such as 23andMe has become ever more mainstream and is predicted to grow to a $340 million industry in the next five years. In fact, earlier this year, the FDA began allowing 23andMe to provide DTC testing for increased risk of 10 conditions, including celiac disease, hereditary hemochromatosis, Parkinson’s, alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency and late-onset Alzheimer’s disease.

However, experts cast a wary eye on DTC testing for a number of reasons. Genetic testing is highly technical and complex and it is still hard to predict who will actually develop common diseases such as diabetes, hypertension, and many cancers from genes alone. For many conditions, a negative DTC test result does not necessarily guarantee low risk because it is believed to be the interaction of complex environmental factors with genes that cause disease. That means all information must be considered in the context of a patient’s environment, lifestyle and family medical history, ideally explored during a one-to-one consultation with a primary care physician.

While there is still much to be uncovered, there is no denying the desire to incorporate personalized medicine in clinical practice is increasing. Scientists are beginning to understand the interplay of genes and environment on disease for about one third of the roughly 20,000 genes we all possess, and the portfolio of knowledge continues to grow rapidly. Even more comprehensive tests that examine numerous genes and variants in an individual’s exome (the protein-making part of the gene), known as next generationgeneration sequencing, will gradually become accessible as the costs associated with them continue to fall. Technologies that enable scientists to alter an organism’s DNA (see below) are being refined. With every advance, we may come closer to realizing the vision of Dr. J. Craig Venter, one of the primary forces behind the original Human Genome project, who said in 2015: “I’m hoping that these next 20 years will show what we did 20 years ago in sequencing the first human genome was the beginning of the health revolution that will have more positive impact in people’s lives than any other health event in history.”

Coming to Terms with Genetic Testing

- Chromosomal microarray: looks for genetic changes in the genome, sometimes caused by an existing medical condition.

- Genome editing: technologies that enable scientists to change an organism’s DNA by adding, removing or altering genetic materials at particular locations in the genome. Gaining favor is the newest CRISPR technology, less expensive and more accurate than other genome editing methods.

- Single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs: the most common type of genetic variation among

people. They can act as biological markers, helping locate genes associated with disease, and may help predict an individual’s response to certain drugs, susceptibility to environmental factors such as toxins and risk of developing particular diseases. SNPs can also be used to track inheritance of disease genes within families.

- Genotyping panels of selected susceptibility variants: often used in DTC genetic tests, and include SNPs that have been associated with common, complex diseases such as type 2 diabetes, autoimmune disease and metabolic traits.

- Specific single gene tests: performed as part of a focused risk evaluation for heritable disease or for diagnostic considerations e.g. BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene sequencing for carrier identification in at-risk individuals with a strong family history of breast cancer.

Source: Up to Date

The post Genetic Testing and Your Health appeared first on Specialdocs Consultants.

by Specialdocs Consultants, LLC | Nov 20, 2017 | Medical Tests, Medications, Patient News

This is the first in a series exploring some of the most promising advances inspired by the Human Genome project. From the burgeoning field of pharmacogenomics to consumer genetic testing such as 23 and Me, the time from discovery to application is progressing rapidly. We’ll look at some of the latest thinking and its impact on personalizing medicine in the future.

To boil down a complex subject to its very human goal, pharmacogenomics means using genomics to get the right dose of the right drug to the right patient at the right time. There is tremendous variability in individual response to drugs, and a large percentage of adverse drug reactions may be due to genetic variables that are just beginning to be really understood.

It’s important to note that while significant progress has been made, the actual use of pharmacogenomics in primary care may be many years away and unlikely to impact the way in which your physician currently prescribes medications for you. However, as research continues to accumulate, the medical community is hopeful that this information will someday help guide prescription decision-making in a much more precise and personalized way.

Did You Know?

1957 – Dr. Arno Motulsky suggests that individual differences in drug efficacy and adverse drug reactions are at least partially attributable to genetic variations

2008 – The Food and Drug Administration releases a table listing genomic biomarkers with established roles in determining drug response

Sources: The National Human Genome Research Project, UptoDate, FDA.gov, JAMA

What we know now

Slightly different, but normal, variations in the human genetic code can yield proteins that work better or worse when they are metabolizing different types of drugs and other substances. Even small differences can have a major effect on a drug’s safety or effectiveness for an individual patient. Your drug-metabolizing enzymes may be set to act in a completely different way than a friend of similar height and weight because phenotypes range from ultrarapid and rapid metabolizers to normal, intermediate and poor metabolizers.

Consider this example from the National Institutes of Health: The liver enzyme known as CYP2D6 acts on 25 percent of all prescription drugs, including the pain reliever codeine. There are more than 160 versions of the CYP2D6 gene, and many of these vary by only a single difference in their DNA sequence. People who manufacture an overabundance of CYP2D6 enzyme molecules metabolize the drug very rapidly, and as a result, even a standard dose can be too much. Conversely, those who carry a CYP2D6 gene that results in a slowly metabolizing enzyme may not experience any pain relief. Armed with this kind of information, a physician may be able to prescribe different types of pain relievers for both of these patients.

The Food and Drug Administration now includes pharmacogenomic information on the labels of some medications, with details on risk for adverse events and side effects, effectiveness for people with specific genome variations, genotype-specific dosing and mechanisms of drug action (the specific biochemical interaction through which a drug substance produces its pharmacological effect). This may eventually help physicians make the right individual patient choices for drugs that include pain relievers, antidepressants, antivirals, statins and blood thinners.

A number of barriers, which includes the lack of clear, evidence-based guidelines, need to be overcome before personalized drug therapy becomes a routine component of mainstream medicine. For now, pharmacogenetics testing is successfully being used in treatment of specific genetically influenced tumors, and for certain medications for cystic fibrosis, inflammatory bowel disease and HIV…important first steps in this promising field.

Defining Terms

- Pharmacogenomics: A field of research focused on understanding how genes affect individual responses to medications.

- Pharmacogenetics: Sometimes used interchangeably with pharmacogenomics, it’s actually a subcategory that refers to the role of genetic variation on response to a drug; can be inherited through the germline or acquired as in a tumor.

- Pharmacokinetics: How a drug moves through an individual’s body, from absorption and distribution through excretion. Blood and urine tests determine where a drug goes and how much of the drug or a breakdown product remains after the body processes it.

The post Unlocking the Genetic Code: Spotlighting Pharmacogenomics appeared first on Specialdocs Consultants.

by Specialdocs Consultants, LLC | Nov 20, 2017 | Healthy Aging, Medical Tests, Patient News

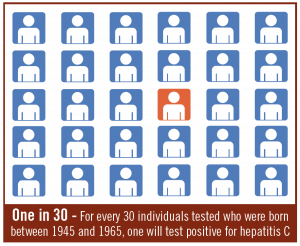

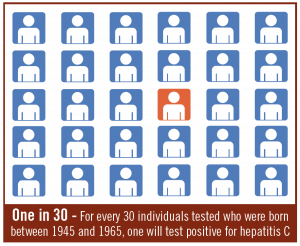

It’s called ‘the forgotten virus,’ but after a sustained advertising campaign and years of strong recommendations for testing by the Centers for Disease Control it’s almost certain that the liver-damaging Hepatitis C will be remembered…and for good reason. All people born between 1945 and 1965 – the Baby Boomer years – are now advised to take a screening test for Hepatitis C virus, the most common bloodborne infection in the United States. The reason? Boomers, born in a time before universal precautions and infection control guidelines were fully established, are five times more likely to have Hepatitis C than other adults, but not likely to be aware of it, as symptoms lay dormant for years. Testing was first recommended for all Boomers in 2013, but less than 15 percent of this at-risk generation have heeded the advice, which means many who are infected remain unaware they carry a potentially fatal but very curable virus.

Below we dispel some of the misperceptions and the breakthrough treatments available today. Most importantly, we explain why scheduling a blood screening is a vital act of prevention, and one we encourage every Baby Boomer to take.

What is hepatitis C?

The common, chronic bloodborne infection known as hepatitis C is caused by the hepatitis C virus, and is a major cause of liver disease.

How does it happen?

The virus causes an inflammation that triggers a slow cascade of damage in the liver, with hard strands of scar tissue replacing healthy liver cells. The liver is no longer able to effectively filter toxins or make the proteins the body needs to repair itself.

Why is testing critical?

Hepatitis C can hide in the body for decades without causing symptoms, while it attacks the liver. Since most people don’t have warning signs of hepatitis C, they don’t seek treatment until many years later, when the damage often is well underway. Left untreated, hepatitis C can result in cirrhosis or liver cancer, and is the leading indication for liver transplant in the U.S. If treated, however, the vast majority of patients can be cured within a few months.

Did You Know?

80% – Of the 3.2 million people affected by chronic hepatitis C, almost 80% were born during the baby boomer generation

10.5 million – Out of 76.2 million Baby Boomers, the number who have been tested for hepatitis C

Sources: American Journal of Preventive Medicine, Centers for Disease Control

Why are Baby Boomers at particularly high risk for hepatitis C?

Once thought of as a disease primarily of drug users, contracted from sharing of needles, hepatitis C can also be contracted through inadequate sterilization of medical equipment and the transfusion of unscreened blood. Boomers grew up before the hepatitis C virus was identified in 1979, so it’s likely that many became infected through medical equipment or procedures before universal precautions and improved infection control techniques were adopted. Others may have been infected from contaminated blood before widespread screening nearly eliminated the virus from the blood supply by 1992.

What is the test for Hepatitis C?

A simple blood test for hepatitis C antibodies will indicate if you’ve been exposed to the virus at some point in your life. If you test positive, further testing will be done to determine if the virus remains in your body, how much is circulating and what specific strain or genotype you have. At least six strains of hepatitis C exist and treatment is based on the specific genotype. Other tests, including ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and a liver biopsy can be performed to identify inflammation and see if any permanent scarring has taken place in the liver.

What treatments are available?

Today’s regimens of direct acting oral antivirals stop the virus from reproducing and clear hepatitis C from the body in a matter of weeks. These breakthrough drugs, first made available in 2013, represent a tremendous step forward in treatment, with a success rate upwards of 95% in those infected with the hepatitis C virus. Medication is targeted to the specific genotype of the virus, and most patients experience few side effects – a vast improvement over previous options of pegylated interferon and ribavirin which caused uncomfortable side effects and were effective less than half the time.

The post Hepatitis C Testing Recommended for All Baby Boomers appeared first on Specialdocs Consultants.

Recent Comments